Puritan Heritage

Nathaniel Hawthorne was born July 4, 1804, in Salem, Massachusetts. He was of the sixth generation of his family in Salem. Shy and bookish, he studied at Bowdoin College then returned to Salem after graduating in 1825.

In many of his works, Hawthorne explores some of the darker aspects of life in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. He portrays the early colonists as irrational, guilt-ridden, and unaccepting of others’ beliefs and viewpoints. Bothered by what he considers the sins of his earliest ancestors in the new world, he carried their guilt in his soul, and sought relief through writing tales and novels.

William Hathorne was the first of that name to arrive in Massachusetts Bay. A good friend of Governor John Winthrop, he was given a grant of land in the town of Salem as an inducement to reside there. William moved to Salem around 1636. In the introduction to The Scarlet Letter, Nathaniel wrote about William:

The figure of the first ancestor, invested by family tradition with a dim and dusky grandeur, was present to my boyish imagination, as far back as I can remember. It still haunts me, and induces a sort of home-feeling with the past … . I have a stronger claim to a residence here on account of this grave, bearded, sable-cloaked, and steeple-crowned progenitor,—who came so early, with his Bible and his sword, and trode the unworn street with such a stately port, … He was a soldier, legislator, judge; he was a ruler in the Church; he had all the Puritanic traits, both good and evil. He was likewise a bitter persecutor; as witness the Quakers, who have remembered him in their histories, and relate an incident of his hard severity towards a woman of their sect, …

— Hawthorne, 1850.

There is some doubt about William’s role. As a member of the Colonial Assembly at the time, he likely voted in favor of the persecution of Quakers, but that is not absolutely certain. As in the later witchcraft mania in Salem Village, the clergy were the ones who aroused public opinion and instigated persecutions; the civil authorities were only the means to the ends that the clergy sought.

William’s son John Hathorne served as a judge in the Salem witch trials. He described himself in his last will as a merchant, not as a lawyer. Historians record that he had at most a minimal legal education, but that didn’t stop him from serving as judge. It was reported that he was the only one who did not repent of his part in that tragedy.

Following what Nathaniel wrote about William, he wrote:

His son, too, inherited the persecuting spirit, and made himself so conspicuous in the martyrdom of the witches, that their blood may fairly be said to have left a stain upon him.

— Hawthorne, 1850.

And on behalf of both William and John, Nathaniel expressed his remorse in the same introduction:

I know not whether these ancestors of mine bethought themselves to repent, and ask pardon of Heaven for their cruelties; … At all events, I, the present writer, as their representative, hereby take shame upon myself for their sakes, and pray that any curse incurred by them … may be now and henceforth removed.

— Hawthorne, 1850.

Early Writings

Nathaniel Hawthorne’s first novel, Fanshawe, was published anonymously in Boston in 1828; shortly afterward, he regretted publishing it and tried to recall all copies. It remains widely available.

After that failure he turned to writing short stories, selling them to magazines when he could. One of these, featuring a talking pump, was titled “A Rill from the Town Pump.” It was first printed in 1835 in the New England Magazine.

Salem’s first fresh water source was a spring near what is now Town House Square at the intersection of Essex Street and Washington Street. In Hawthorne’s time, there was a hand-operated pump from which water could be drawn from a well supplied by the spring.

The town pumps of Hawthorne’s day were famous affairs. Heavily framed in stone and furnished with wooden troughs, and often built in pairs, with a handle projecting at either side, they were seen in various sections of the town, stationed over wells, in suitable locations, where the public could freely help themselves to the pure water they dispensed.

Hawthorne had a curious pride in this early and popular effort.

— Hunt, 1916.

The well was destroyed in 1839 during construction of the train tunnel beneath the square. Another well was set up on Washington Street in the passageway between the First Church (now Rockafellas) and the adjacent bank building (now Ledger Restaurant). No public well or pump remains at the site, though a fountain nearby commemorates both the old pump and Hawthorne’s short story.

A rill is a small stream, and Hawthorne uses it as a metaphor for a speech delivered by the pump. The pump starts its tale with an exposition of its noble duties and responsibilities, then offers its water as a beverage to all passersby, including a pair of oxen. Eventually the speech decries the evil of alcoholic beverages and promotes temperance and drinking its own good fresh water. Along the way it tells of the history of this source of water:

In far antiquity, beneath a darksome shadow of venerable boughs, a spring bubbled out of the leaf-strewn earth in the very spot where you now behold me on the sunny pavement. The water was bright and clear, and deemed as precious, as liquid diamonds. The Indian sagamores drank of it from time immemorial, till the fatal deluge of firewater burst upon the red men, and swept their whole race away from the cold fountains. Endicott and his followers came next, and often knelt down to drink, dipping their long beards in the spring. The richest goblet, then, was of birch bark. Governor Winthrop, after a journey afoot from Boston, drank here out of the hollow of his hand. The elder Higginson here wet his palm, and laid it on the brow of the first town-born child. … Finally, the fountain vanished also. Cellars were dug on all sides, and cartloads of gravel flung upon its source, when oozed a turbid stream, forming a mud puddle at the corner of two streets. In the hot months, when its refreshment was most needed, the dust flew in clouds over the forgotten birthplace of the waters, now their grave. But, in the course of time, a Town Pump was sunk into the source of the ancient spring; and when the first decayed, another took its place—and then another, and still another—till here stand I, gentlemen and ladies, to serve you with my iron goblet. Drink, and be refreshed!

— Hawthorne, 1837.

Near the end of its tale, the town pump also makes a prediction and a suggestion:

My dear hearers, when the world shall have been regenerated by my instrumentality, you will collect your useless vats and liquor casks into one great pile, and make a bonfire in honor of the Town Pump. And when I shall have decayed, like my predecessors, then, if you revere my memory, let a marble fountain, richly sculptured, take my place upon this spot.

— Hawthorne, 1837.

Hawthorne published his first collection of short stories, Twice Told Tales, in 1837. It contained sixteen stories including “A Rill from the Town Pump.” An expanded second version of the collection came out in 1842, containing the original sixteen and sixteen new short stories. Twice Told Tales was Hawthorne’s first successful book, yet it brought him little financially. Hawthorne lacked all knowledge of business; he also lacked the skill and attitude to negotiate for a fair compensation. Despite being well-known, he struggled to support his family with his income from writing.

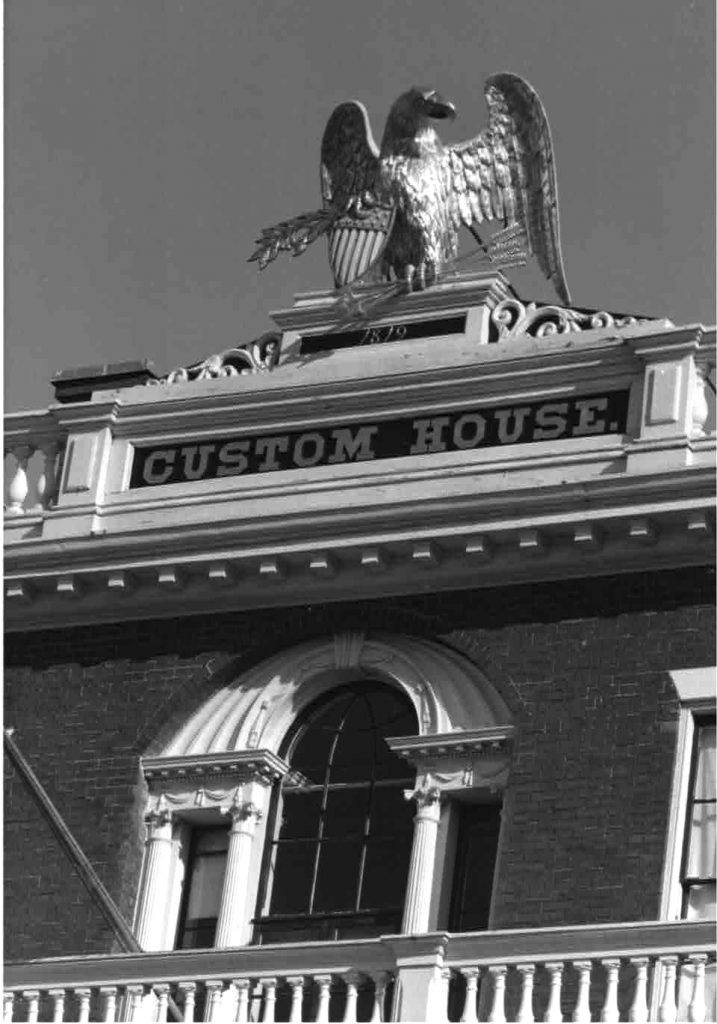

In 1846, his best friend and future President of the United States, Franklin Pierce, along with other friends in the Democratic Party, secured the position of Surveyor in the Salem Custom House for Hawthorne. But following the change in administration to the Whig Party in 1848, and a lengthy fight to continue as Surveyor, Hawthorne lost that job.

Facing the prospects of struggling to support his family again, he poured the betrayal and pain he felt into his first great novel, The Scarlet Letter. It was published in 1850, just after he left Salem and moved his family to Lenox. But he did not leave without a recounting of his time in the Custom House:

In the delightful prologue to [The Scarlet Letter], entitled The Custom-house, he embodies some of the impressions gathered during these years of comparative leisure (I say of leisure because he does not intimate in this sketch of his occupations that his duties were onerous). He intimates, however, that they were not interesting, and that it was a very good thing for him, mentally and morally, when his term of service expired—or rather when he was removed from office by the operation of that wonderful “rotatory” system which his countrymen had invented for the administration of their affairs. This sketch of the Custom-house is, as simple writing, one of the most perfect of Hawthorne’s compositions, and one of the most gracefully and humorously autobiographic.

— James, 1879.

The prologue of The Scarlet Letter ends with a farewell message to Salem:

Soon, likewise, my old native town will loom upon me through the maze of memory, a mist brooding over and around it; as if it were no portion of the real earth, but an overgrown village in cloudland, with only imaginary inhabitants to people its wooden houses, and walk its homely lanes, and the unpicturesque prolixity of its main street. Henceforth it ceases to be a reality of my life. I am a citizen of somewhere else. My good townspeople will not much regret me; for—though it has been as dear an object as any, in my literary efforts, to be of some importance in their eyes, and to win myself a pleasant memory in this abode and burial-place of so many of my forefathers—there has never been, for me, the genial atmosphere which a literary man requires, in order to ripen the best harvest of his mind. I shall do better amongst other faces; and these familiar ones, it need hardly be said, will do just as well without me.

— Hawthorne, 1850.

It may be, however,—O, transporting and triumphant thought!—that the great-grandchildren of the present race may sometimes think kindly of the scribbler of bygone days, when the antiquary of days to come, among the sites in the town’s history, shall point out the locality of THE TOWN PUMP!

Sources

Hawthorne, Nathaniel. Twice Told Tales. 1837.

———. The Scarlet Letter. 1850.

Hunt, Thomas Franklin. Visitor’s guide to Salem. Salem, Mass.: The Essex institute, 1916.

James, Henry. Hawthorne (English Men of Letters Series). London: Macmillan and Co, 1879.

Stearns. Frank Preston. The Life and Genius of Nathaniel Hawthorne. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company. 1906.